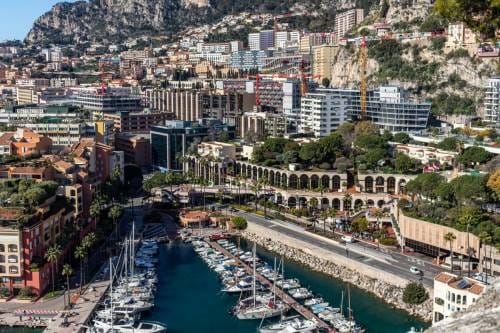

The aura of Monaco is one of glittering opulence and timeless tradition. Yet behind its legendary façades lies a legal confrontation that has quietly erupted. The question is: should Monaco recognize a same-sex marriage performed abroad?

The Case that Stirred the Principality

On 18 March 2024, Monaco’s highest court — the Court of Revision — delivered a stark ruling: a same-sex union contracted in the United States could not be transcribed into Monaco’s civil registers. The judgment declared such registration “contrary to Monegasque international public policy,” overturning earlier rulings by lower courts that had favoured recognition.

The couple at the centre of the dispute are a Monegasque national, and a U.S. citizen. Married in the U.S. they later relocated to Monaco and sought to have their marriage officially recorded in the Principality. After rejection by the Public Prosecutor, success in the Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeal, the matter was escalated, ultimately ending in legal reversal by the Court of Revision, Monaco’s highest court.

The Court’s reasoning did more than deny transcription: it affirmed that Monaco is not obligated under Articles 8, 12, and 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) to register same-sex marriages. Instead, it accepted Monaco’s position that the alternative legal structure , the civil solidarity contract (contract de solidarité civile), provides a legally protective, albeit more limited, status. In short: the state argued that denying marriage transcription is acceptable so long as an alternate legal option exists.

Now, the case has been referred to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), challenging the question: is Monaco’s legal architecture compatible with evolving European norms, or is it an outlier determined to preserve tradition?

Between Law and Norms: The Monaco Response

Monaco has never legalized same-sex marriage under its domestic civil code; same-sex unions, as defined by marital status, remain unrecognized. Yet in late 2019, the Principality moved to adopt a form of legal recognition: the civil solidarity contract, enacted by Law 1.481, which went into force in June 2020.

These contracts allow both same-sex and opposite-sex couples to agree on certain legal rights: property arrangements, social security access, and inheritance benefits, among others. But crucially, they do not establish family status, parental or adoption rights, or full recognition as a marriage in the civil registry.

Monaco, then, has adopted a model of limited legal recognition, in effect, providing protections in some domains, while reserving the full institution of marriage for a traditional framework. This delicate legal compromise is central to how Monaco justifies the refusal to transcribe same-sex marriages.

A Break from Legal Tradition — or Continuity?

To many legal observers and members of Monaco’s own political class, the 2024 ruling represented a sharp rupture. Previously, Monegasque courts used what is known in comparative law as attenuated international public policy. In practice, this allowed foreign marriages or legal arrangements, even if divergent from domestic norms, to be recognized, provided they did not flagrantly violate Monaco’s core legal values.

One historical example still cited: in the 1980s, a man had entered into a bigamous marriage abroad (a practice banned in Monaco). His attempt to divorce was contested on the basis that the second marriage had no standing in Monaco. But the courts ultimately accepted the foreign marriage for the divorce, reasoning that while bigamy violated Monegasque public order, the foreign union still merited acknowledgment under attenuated public policy.

But in the same-sex marriage case, lower courts had treated the foreign union as equivalent to any heterosexual marriage — consistent with that previous legal openness. The Court of Revision’s decision changed that trajectory, rejecting the notion of attenuated public policy in favour of a stricter posture. Critics in Monaco describe the shift as a legal backpedal.

The European Crucible: ECHR and the Pressure of Precedent

Monaco’s invocation of the civil solidarity contract as a protective legal framework is likely to come under heavy scrutiny at the ECHR. In Oliari and Others v. Italy (2015), the European court held that states must provide legal recognition for same-sex relationships, even if not through full marriage, because denying any recognition amounted to a violation of Article 8 (right to private and family life).

That said, the ECHR has historically declined to compel states to legalize same-sex marriage per se. In Schalk & Kopf v. Austria (2010), the court upheld that Article 12 (the right to marry) does not oblige signatory states to open civil marriage to same-sex couples.

Thus, the ECHR judgment may not force Monaco to enact same-sex marriage, but it could very well conclude that the Principality’s refusal to register a foreign same-sex marriage, despite existence of a legal alternative, constitutes discrimination or disproportionate restriction.

If the ECHR rules against Monaco, the Principality might be compelled to amend its laws, not necessarily by legalizing same-sex marriage at home, but by recognizing foreign same-sex unions in civil registries or via a parallel structure.

The Broader Landscape and Stakes

Monaco is not alone in this delicate balancing act. Across Europe, a patchwork of laws is emerging: many states now permit same-sex marriage; others provide civil unions or registered partnerships; and some maintain restrictive regimes.

Critics of Monaco’s approach note that while civil solidarity contracts are a step forward, they stop short of equal treatment. For instance, spouses under such contracts cannot adopt or share full marital rights. Moreover, critics argue such contracts create a legally second-class status.

Among Monegasque civil society and a few political voices, the current moment is viewed as pivotal. If the ECHR approves a claim, Monaco could face pressure to align with a European consensus that increasingly favours equitable treatment of same-sex unions.

The Human Equation

Beyond legal arguments, this is a deeply personal controversy confronting identity, dignity, and belonging.