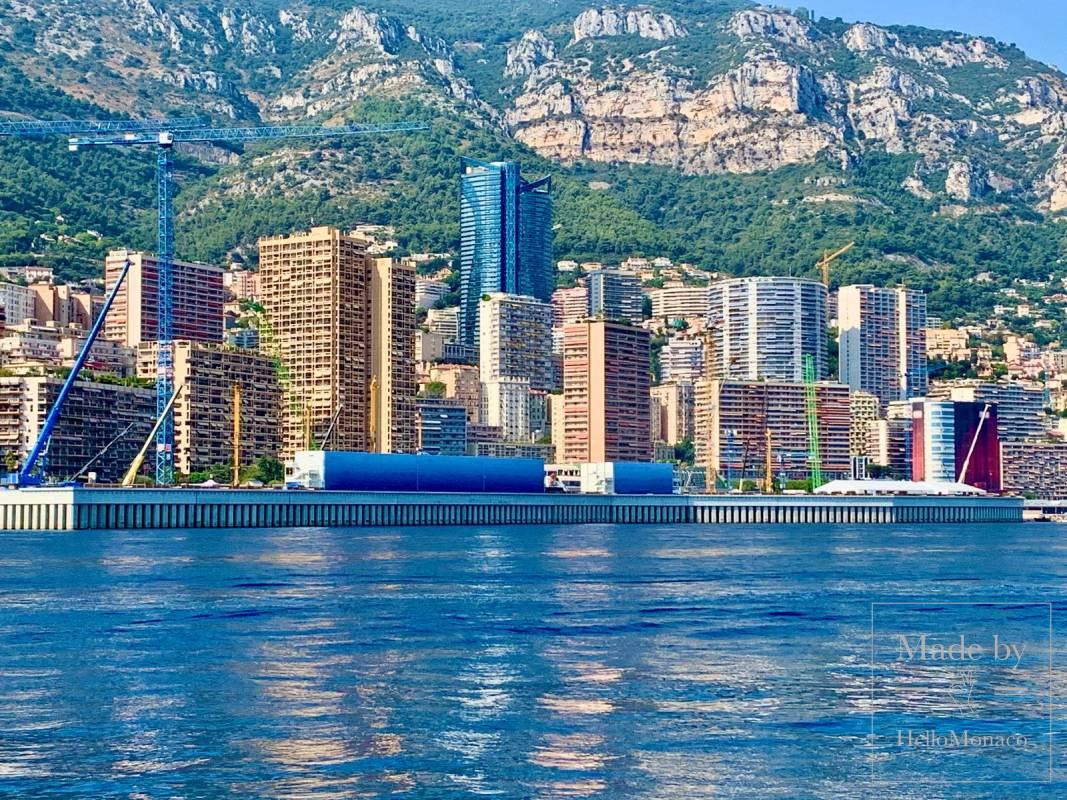

When one thinks of Monaco, images of the Grand Prix and sparkling Mediterranean vistas come to mind. Yet another story quietly unfolding in the Principality is the one of pay-equality between women and men: subtle, incremental but significant nonetheless.

A snapshot of where we are

The national statistics institute IMSEE has just published its second major study (data from 2024) on wage gaps between women and men in Monaco. Here are some of the key findings:

In the public sector, women’s average indexed pay now surpasses that of men by 2.4%, up from 0.7% in 2019. In the private sector, average monthly male salaries are 18.6% higher than for women in 2024, still a large gap, though improved from 28.5% in 2019.

When analysed by median salary in the private sector (which removes the influence of extreme high or low values), the gap falls to just 0.1%, virtually parity.

In short: there is real progress — but also real complexity.

Why “progress” is not the whole story

It’s tempting to say “mission accomplished”, but the deeper layers reveal why the story is more than just numbers.

Average vs. Median

The headline number of 18.6% hides the fact that extreme salaries (very high pay for some men) inflate the average. The median measure shows near parity (0.1%), but median only tells you the “middle” of the distribution, not what happens at the top or bottom.

This signals: while many are doing equally, some are still lagging, and some are way ahead.

Structural/non-measured factors

Economists caution that a wage gap doesn’t necessarily imply direct discrimination. As Pierre‑André Chiappori (a former economist who advises the government) points out: you must account for factors like education level, working time, overtime, sector, seniority, job type.

For example: Men do more overtime on average, which increases their pay. Different job sectors may pay vastly different wages. Career interruptions (e.g., for childbirth) impact trajectories.

So, even though pay equality in median looks strong, underlying dynamics still require attention.

Persistent hidden biases & roles

Even with improved numbers, cultural and structural barriers remain. As Céline Cottalorda, the delegate for women’s rights in Monaco, explains: from childhood, girls and boys are often guided (sometimes unconsciously) into different roles, shaping study-choices, career paths, and confidence levels.

Also: mental load, domestic logistics (childcare etc) still disproportionately fall on women, which affects their career progression.

In short: while the “gap” may shrink, the underlying “ladder” still has missing rungs.

Monaco’s unique context

Monaco is small. Many companies are small. The private sector is specialised (luxury, finance, tourism). That context changes how wage-inequality plays out.

Because most companies are “very small”, imposing broad legal or index-based measures is harder. The government chooses incentive and education-based approaches rather than coercive ones.

The public sector in Monaco shows a remarkable trend: women earning more on average than men. This is quite rare globally and signals strong progress in public employment.

Monaco’s near-parity in median private salaries places it ahead of many European countries: e.g., France’s gap in 2023 was about 6.2% in favour of men.

Thus, Monaco offers a case study: small size, good progress, but still a lot to unpack.

What’s next? The agenda for change

If one were crafting a roadmap for further change, the study and commentary suggest several key action-areas:

Data upgrade & transparency: The IMSEE dataset does not yet fully cover individual education, career breaks, promotion path, etc. Filling those gaps will give a clearer picture of “unexplained gap”.

Focus on negotiation & networks: Because salary negotiation and networks tend to favour men, training programmes like Monaco’s “L’Effet A” (aimed at women in the public sector for negotiation/self-confidence) are promising.

Encouraging equal career breaks / childcare support: To reduce the impact of interruptions or domestic responsibilities on women’s career paths.

Cultural change from school-age: Encouraging girls (and boys) to explore full range of studies and careers, breaking role-assignment early.

The Final Frontier

While the median gap is near zero and that is a headline win, it would be wrong to conclude “problem solved”. The average gap still exists; structural issues still matter; career trajectories still show gendered patterns. Monaco’s size and context mean it’s easier in some ways, but harder in others (small firms, informal practices). The figures don’t always tell the whole story.

The next frontier is less about “closing the gap” and more about equalising opportunity, career path, seniority, and transparency.